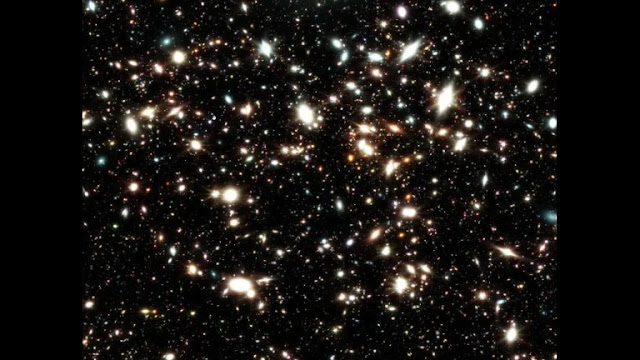

This view of a portion of the DREaM simulated galaxy catalog provides a snippet of sky that might correspond, statistically, with what James Webb expects to see. This particular snippet showcases an incredibly rich region of relative nearby galaxies clustered together, which could provide Webb with an unprecedented view of galaxies magnified by strong and weak gravitational lensing. Even this simulated view, however, omits the majority of galaxies: too faint and distant to even be seen with JWST, the Nancy Roman Telescope, or any hitherto proposed present or future mission. (Credit: Nicole Drakos, Bruno Villasenor, Brant Robertson, Ryan Hausen, Mark Dickinson, Henry Ferguson, Steven Furlanetto, Jenny Greene, Piero Madau, Alice Shapley, Daniel Stark, Risa Wechsler) We're not even a dust mote in a vast reality we will never fully understand. As tech advances, the size of the universe/multiverse gets ever larger to the degree the esteemed Carl Sagan could have never imagined when writing Billions & Billions back in 1997.

The Universe is a vast place, filled with more galaxies than we’ve ever been able to count, even in just the portion we’ve been able to observe. Some 40 years ago, Carl Sagan taught the world that there were hundreds of billions of stars in the Milky Way alone, and perhaps as many as 100 billion galaxies within the observable Universe. Although he never said it in his famous television series, Cosmos, the phrase “billions and billions” has become synonymous with his name, and also with the number of stars we think of as being inherent to each galaxy, as well as the number of galaxies contained within the visible Universe.

But when it comes to the number of galaxies that are actually out there, we’ve learned a number of important facts that have led us to revise that number upwards, and not just by a little bit. Our most detailed observations of the distant Universe, from the Hubble eXtreme Deep Field, gave us an estimate of 170 billion galaxies. A theoretical calculation from a few years ago — the first to account for galaxies too small, faint, and distant to be seen — put the estimate far higher: at 2 trillion. But even that estimate is too low. There ought to be at least 6 trillion, and perhaps more like 20 trillion, galaxies, if we’re ever able to count them all. Here’s how we got there.

This snippet from a structure-formation simulation, with the expansion of the Universe scaled out, represents billions of years of gravitational growth in a dark matter-rich Universe. Note that filaments and rich clusters, which form at the intersection of filaments, arise primarily due to dark matter; normal matter plays only a minor role. However, the majority of galaxies that form are faint and far away, rendering them invisible within the limitations of our current telescopes. Credit: Ralf Kaehler and Tom Abel (KIPAC)/Oliver Hahn)

Read Big Think's detailed piece to see why we are not even a dust mote in the grand scheme of things.

No comments:

Post a Comment