Illustration by Gérard DuBois

Heresy, you know, the notion of expressing an idea contrary to church doctrine, especially in the 1600s, was a most dangerous undertaking, especially when the inquisition was in charge of questioning the validity of said idea, the most famous of which being Galileo's support of heliocentrism, the astronomical model in which the Earth and planets revolve around the Sun at the centre of the universe, a stunning rebuke to the 1500 year old church support of the Ptolemaic theory of earth being the center of the universe and not the sun. Needless to say, this affront would not stand so the inquisition tried and condemed Galileo for heresy, thus forcing the scientist to recant his findings before being placed under house arrest for the rest of his life. With this in mind, it seems appropriate Sam Alito would fit right in as an inquisitor based on the zealotry expressed by this jurist on all things concerning a woman's right to choose.

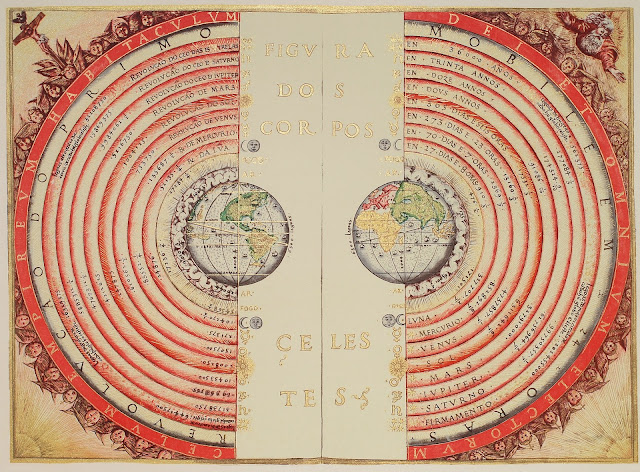

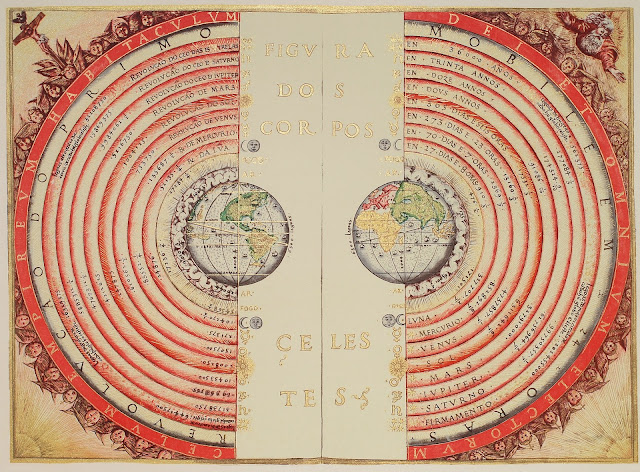

Figure of the heavenly bodies — An illustration of the Ptolemaic geocentric system by Portuguese cosmographer and cartographer Bartolomeu Velho, 1568 (Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris)

Now, though, Alito is the embodiment of a conservative majority that is ambitious and extreme. (He declined to be interviewed for this article.) With the recent additions of Brett Kavanaugh and Amy Coney Barrett to the Court, the conservative bloc no longer needs Roberts to get results. And Alito has taken a zealous lead in reversing the progressive gains of the sixties and early seventies—from overturning Roe v. Wade to stripping away voting rights. At a Yale Law School forum in 2014, he was asked to name a personality trait that had impeded his career. Alito responded that he’d held his tongue too often—that it “probably would have been better if I said a bit more, at various times.” He’s holding his tongue no longer. Indeed, Alito now seems to be saying whatever he wants in public, often with a snide pugnaciousness that suggests his past decorum was suppressing considerable resentment.

In July, Alito, who is seventy-two, delivered a speech at the Palazzo Colonna, in Rome, for a gathering hosted by the University of Notre Dame Law School’s Religious Liberty Initiative—a conservative group that has filed amicus briefs before the Court. (Faculty affiliated with the group also filed briefs in Dobbs. Legal analysts at Slate noted that the spectacle of a Justice “chumming it up with the same conservative lawyers who are involved in cases before the court creates the unseemly impression of judicial indifference toward basic judicial ethics rules.”) Alito had donned stylish horn-rimmed glasses that he doesn’t usually wear in public, and he had a new, graying beard. Though the speech focussed on one of his favorite topics—the supposed vulnerability of religious freedom in increasingly secular societies—he couldn’t resist crowing about Dobbs. “I had the honor this term of writing, I think, the only Supreme Court decision in the history of that institution that has been lambasted by a whole string of foreign leaders,” Alito said. “One of these was former Prime Minister Boris Johnson—but he paid the price.” (Johnson resigned earlier this summer.)

Galileo before the Holy Office, a 19th-century painting by Joseph-Nicolas Robert-Fleur

No comments:

Post a Comment