The Atlantic

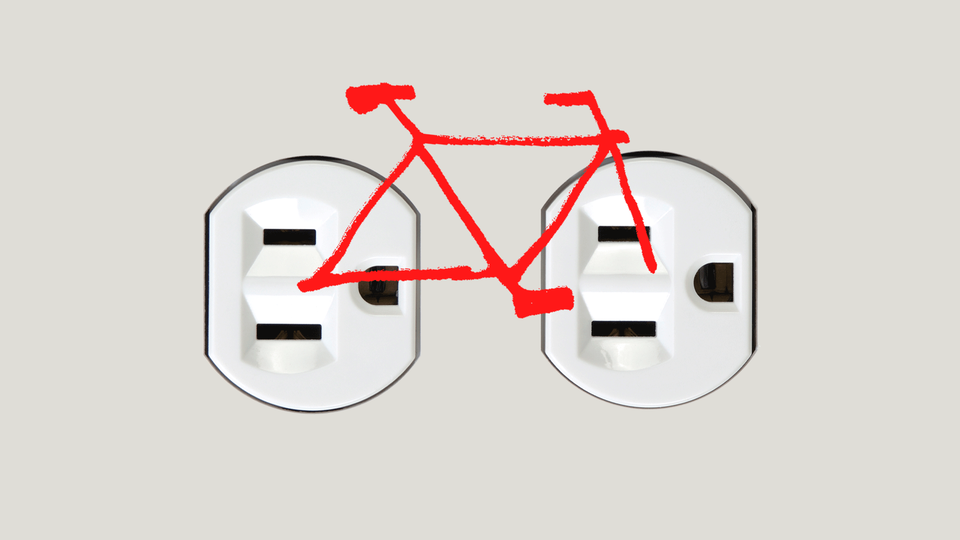

I cycle. My son turned me onto the sport back in 1992 and I've been on the road ever since as cycling is like Zen: Head moving through space being in the world but not of it while pedaling with intense effort traversing hills and dealing with headwinds. (The Zen archer comes to mind here.) Waxing poetic about cycling is cool but this piece isn't about riding but rather about the first law of thermodynamics, you know, the one stating energy can never be created or destroyed, only transformed.

In cycling, you feel this transformation process happening all the time; go up a hill, potential energy increases, going down the hill, potential coverts to kinetic, thus showing the rider first hand how energy works in the real world. When coupled with quantum, chaos and relativity, the power of the first law and how it drives reality becomes really interesting... Monday, June 21, 2010/BRT

Now, contrast this with the E-Bike ...

In my experience, e-bikes are also strange to ride, and that strangeness contributes to their oddity. Having a motor changes a lot of things about a bike. Anytime you pedal with the motor engaged, it will push you forward more than you’ve pedaled. I thought I’d acclimate to it, but I still haven’t; especially when pedaling from a coast out of a turn, I forget the motor is in gear, and when it engages it sends me off course, flying into the curb (or worse, into traffic). The e-bike rolls into an uncanny valley, the chasm between a bicycle under my human power and a motorbike piloted directly by a throttle.

E-bikes’ identity crisis might seem like the symptom of a transition: As soon as adoption really takes off, all of these issues could work themselves out. But I’m not so sure. Something is ontologically off with e-bikes, which time and adoption alone can’t resolve. Whether as bicycles haunted by motorbikes or as mopeds reined in by bikes, e-bikes represent not the fusion of two modes of transit, but a conflict between them.

No comments:

Post a Comment